Yesterday morning I headed out to Kisai High School in Kazo City. It’s only about 20 km away as the crow flies, but between trains, buses, and a bit of footwork it took about an hour and a half to get there.

Kisai High School is where 1260 people from Futaba-machi were moved after leaving Saitama Super Arena at the end of March. It now houses almost everyone from town except those who needed more intensive care in hospitals or seniors’ centers. Kisai High School was closed in 2007, so it’s available indefinitely, and has been refurbished for long-term residence.

While I was handing out shoes and bags the Arena two weeks ago, several men had struggled to try on our sad selection of three women’s belts. I didn’t know if they were still accepting donations at Kisai, but I brought along two of my belts, intending to bring more appropriate donations when I had a better idea of their needs.

I found the volunteer registration desk on the second floor by the school entrance. Arriving a little after 8:00 a.m., they said they’d already closed registration, and had all the volunteers they’d need for the immediate future. Futaba-machi officials were now able to take a more direct role, so less volunteers were needed. So I asked if they were at least accepting donations, and I was introduced to a little man in the old principal’s office down the hall.

The man asked me to write down my name and address on a sheet of paper. As I wrote, I asked him how the new space was working out. He said that it lacked the environmental controls they’d had at the Arena (most Japanese schools have no heating or cooling outside the staff room), but it was a better living space. When I ask how the people were doing, he looked a little sad and said, “They just want to go home.”

“The old people… they know they’ve only got a little time left anyway. They want to spend it at home.”

I asked him how close Futaba-machi had been to the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant, and he said vaguely that it was within ten kilometers. I just checked Google Maps. Futaba-machi’s town hall is 2 km from the plant.

I noted that they were looking at a process of months to cool the reactors, and the man said that they’d probably have to figure out how to restart from here.

Saitama Super Arena was essentially a hub—there’s a shopping mall next door, and it’s only one station away from downtown Omiya. Kisai High School is in the middle of nowhere. It’s on a broad country highway dotted with a few faded restaurants and shops, with the nearest bus stop a ten-minute walk away. The 20-minute ride to the station is a vista of vacant rice fields and lonely old houses. Beyond relying on aid, I’m not sure what those people are going to be able to do.

“People just want to go home.”

It was only then that I twigged as to why this man seemed so tired and so sad. “Hang on,” I said. “Are you an evacuee too?”

“I’m the Secretary of Public Relations.”

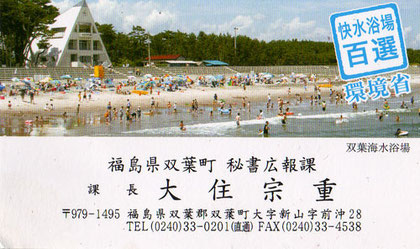

Then he handed me a business card with a picture of a beautiful little beach on it. In Japan, when you receive a business card, it’s normally polite to make a comment about some unique feature. I couldn’t say anything. That beach doesn’t exist any more.

The zero-level for nuclear particles is taken as ten half-lives. For cesium-137, that’s 300 years. Japan’s pretty inventive. Maybe they’ll figure out a way to clean it up. But there’s a good chance nobody will be able to set foot on that beach again in our lifetime.

The man’s name was Ōsumi. He said they were reproducing all the town records by hand because they didn’t have enough computers. The main problem they’re having is the breakdown of families—in the open space, there are no boundaries, and no place in which to enforce rules. The kids are just wandering. There are roughly 200 children in the group. The younger kids are being integrated into local schools, but Japan has a very complicated system for high school selection, basically equivalent to university entrance overseas, and the older students are going to take more time.

I asked what I should do about my donation, and Ōsumi-san said he’d bring it around himself. So I handed Futaba-machi’s Secretary of Public Relations my two pathetic belts, and he wrote down my details with obsequious formality.

In the entranceway, the volunteers for the day had assembled for their 9:00 start. Identified by their yellow hats, they would mostly be involved with cleaning. I spoke to a young man who’d registered by phone just the night before. He said he was also involved in a small NPO that normally does musical performances for people with mental disabilities, and is now operating in the north. When they get back, he’s hoping to get the group to come to Kisai. An entertainer friend of mine is up north this weekend doing the same.

There’s a bus roughly every thirty minutes out of Kōnosu Station on the Takasaki Line. To inquire about volunteering, call the Kazo City Hall at 0480-62-1111.

Ōsumi-san had said there were also an American and a New Zealander in the group, local teachers who had been evacuated along with everyone else. It was only on the train on the way home that I realized that I should have asked if they needed help with translation.

From there I went straight to Second Harvest. Not even bothering to ask if they needed help, I just started picking things up, packing and sorting.

I got to know some of the regular volunteers while helping out with a few hundred dishes after the weekly soup kitchen they put together for the homeless in Ueno Park. They all came by to help load the trucks after they were done.

One of the organizers is a classic salty-dog, sixty-plus and perpetually dissatisfied with the amateur antics of the newbie volunteers around him, though he offers an obscure joke as often as he drops a complaint. I ended up helping him with a few tasks, generally screwing up the first time but listening and learning. At the end of the day he offered me a handshake, which was probably the greatest compliment I could have received.

At the same time, some friends of mine were walking 7.5 hours around the Yamanote Line in Tokyo to raise money for Civic-Force*, one of the first aid groups to be on the ground in the north (*or for Oxfam, as you will note in Ben's correction below). For those who are interested, they’re still accepting donations.

I just picked up all the Peace Boat stuff and jammed it in the closet. It’s the first time I’ve seen my floor in weeks.

Write a comment

Ben (Sunday, 10 April 2011 10:44)

Mike, much as I enjoy reading your blog, I do wish to (gently) correct just one point.

The Yamathon was an event organised by a member of a volunteer group, the IVG. The IVG are a small group, but with big ideas. They work really hard to raise money for Oxfam Japan. I took part in the Yamathon to show my support for Oxfam Japan, and the IVG.

Another group of friends decided to use the Oxfam event to fundraise for a different organisation that they felt needed support. I am impressed with their efforts, and think it was great that they took part. I was very happy to learn that they raised a lot of money for 'Civic Force.' However, the team I was in, which finished in 7.5 hrs, were raising money for Oxfam Japan.

breitling replica (Friday, 30 January 2015 06:59)

Of all blogs that accept arrested the above topics , I , is enlightening in practice this .