The Divine Comedy is not at all what you would expect to find upon opening a 700-year-old extension of Biblical scripture.

The Comedy was written between 1308 and 1321, after Dante was exiled from Florence by decree of Pope Boniface VIII, who had the anti-papal White Guelphs, a political party of which Dante was a member, expelled from the city. The result? A biting, analytical and scathingly political document, with a prevailing conviction that the early fourteenth century was a time in need of immediate divine remediation.

While a third of the Comedy's content is of Biblical inspiration, the remaining two thirds form a political satire and fan-fiction archive that, considering the Medieval obsession with Greek and Roman literature, is little different at heart from any work of derivative fiction that might be produced today.

It must be noted that, by official interpretation, the Divine Comedy is a ‘comedy’ only in the classical sense, where all stories were defined as either ‘comedy’ or ‘tragedy’. It was written in the vernacular, and the protagonist was better off at the end than he was at the beginning, thus distinguishing it from the high language and sad ending required of a ‘tragedy’. Looking at the text in the modern sense of the word, however, one might argue that ‘comedy’ is the entirely apt term—if it is taken to mean ‘political satire’.

Political Satire

Dante stops to talk to the denizens of every realm he visits throughout his first-person journey from Hell to Heaven. Half of these people are political and religious figures from the thirteenth century, many of them so obscure that the reader has to regularly flip to the endnotes—a copious collection as long as the text itself—or be content to remain in a constant state of ignorance. Monks, cardinals, nobles, heroes and political figures—even some of Dante’s friends and ancestors—crop up variously to enjoy exaltations and suffer humiliations.

Dante starts by tossing half a dozen popes straight into Hell. Right at the outset he encounters Pope Celestine V (1215-1296), who, having abdicated the papacy, now shambles about the Vestibule of Hell, the outer circle of the uncommitted and the pusillanimous. Next is Pope Anastasius II (pontiff during a time of schism in the 6th century), who is found in a burning tomb in the Sixth Circle of Heretics and Sceptics. He resides near Frederick II, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 1212-1250, frequently at war with the papacy.

In the Eighth Circle of Hell, Dante finds the feet of Pope Nicholas III (died 1280), who has been stuffed head-first into a hole in the chasm of the simoniacs (those who demanded payment for sacraments or holy offices). The dead pontiff anticipates the arrival of Popes Boniface VIII (1235-1303, the pope who exiled Dante) and Clement V (1264-1314), who, while still alive at the time of the story, are prophesied to be shoved in right after Nicholas III as soon as they die.

The author regularly pauses in his storytelling to berate the entire city of Florence for its excesses, as well as to find fault with any other region of Italy he’s irritated with. In between, he finds time to knock out asides at contemporary preaching:

|

Christ did not say to his first companions: “Go and preach rubbish to the world”; But gave them truths that they could build upon.

—Paradiso XXIX |

And contemporary life:

|

So, if the present world is going off course, The reason is in you, and should be sought there; And I will tell you truly how the land lies.

—Purgatorio XVI |

In the second chasm of the Eighth Circle of Hell, paramours and flatterers drown in shit, reminding me of Swift’s faux-ingenuous recommendation (via Gulliver) that certain politicians try eating shit for their health. There's even a dry laugh to be found in Hell’s final pit of Cocytus, in the zone of traitors to country and cause, where Dante is startled to encounter the frozen form of a man whom he knows to be still alive. The man explains,

|

Know, that as soon as any soul betrays,

As I did, then his body is taken from him By a demon, who afterwards governs it Until his time on earth comes to an end.

—Inferno XXXIII |

Fan Fiction

Dante is guided through Hell and Purgatory by Virgil, whose works were considered the height of literary achievement at the time (Interestingly, while his name was known, Homer was considered a secondary poet as his greatest works had yet to be translated). In addition to Virgil and Homer, Dante meets Aristotle, Socrates and Plato—as well as Aeneas, legendary founder of ancient Rome and subject of Virgil’s Aeneid—in Limbo, the first Circle of Hell, the circle of good pagans.

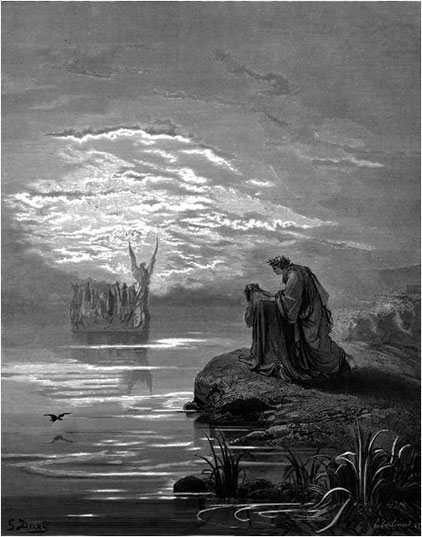

From there, Dante conflates Greek and Roman mythology with popular myth, Biblical scripture and actual history to design and populate his conception of the Inferno. Beyond the Inferno, Dante's version of Purgatory is completely made up: it is a mountain diametrically opposite to Jerusalem, in the centre of the ocean that was believed to take up the lower half of the Earth, where mankind is purged of the Seven Deadly Sins one level at a time. From Mt. Purgatory, Paradiso aims to associate different virtues with the Ptolemaic conception of the heavens.

Christian Hell with Greek Rivers

From the Vestibule of Hell, Charon (of the Greek myth) rows the dead across the River Acheron to Limbo. Acheron, the river of sorrow, is one of five rivers in Hades, all of which are appropriated for the Comedy.

In the Fifth Circle of Hell, the souls of the wrathful are subsumed in the River Styx (the Greek river of hate, more of a marsh in Dante's version), while in the Seventh Circle the River Phlegethon (the Greek river of fire) is converted into a river of boiling blood, where centaurs (yes, centaurs) shoot arrows into any soul who emerges from his punishment for violence against his fellow man, most notably Alexander the Great and Attila the Hun.

Cocytus, the Greek river of lamentation, is the name given to the lowest pit of Hell, a frozen lake in which the traitorous are trapped for eternity. The River Lethe, the river of forgetfulness, is reserved for Earthly Paradise atop Mt. Purgatory, where mortals are bathed to forget their sins. To replace Cocytus as a river, Dante makes up a river of his own—the Eunoe—which conjoins with Lethe and has the property of reinforcing the memories of good deeds prior to ascent into Heaven.

Legendary Greeks and Arthurian Knights

According to Dante, Minos, the legendary king of Crete who sent people to be eaten by the Minotaur in his labyrinth, sits in Limbo as the judge of the dead, determining which circle of Hell each soul should be sent to. This is adapted from Virgil, who had Minos determine whether dead souls went to Elysium or Tartarus.

The most bizarre mix is in the Second Circle of the Sexually Promiscuous. Here Dante finds Helen of Troy, Paris and Achilles alongside Sir Tristram and Cleopatra, all while Dante hears the story of an adulterous woman who was slain by her husband in a jealous rage during Dante’s youth.

Further down, three-headed Cerberus awaits in the Third Circle of the Gluttonous. Furies and Gorgons occupy the City of Dis, the gate to Lower Hell. The Minotaur hangs out in the Seventh Circle of the Violent, and Harpies perch in the Forest of Suicides. Geryon, a grandson of Medusa, gives Dante and Virgil a lift between the Seventh and Eighth Circles.

In Malebolge, the Eighth Circle of Fraud, Jason of the Argonauts is whipped by demons in the chasm of procurers and seducers. For devising the Trojan Horse, Ulysses and Diomedes are subsumed in pillars of flame in the chasm of corrupt advisers. Biblical characters are present as well—Caiaphas, the high priest who ordered Christ’s crucifixion, is crucified on the ground and trampled in perpetuity in the chasm of hypocrites.

The Greek giant Antaeus lowers Dante and Virgil into Cocytus, the Circle of Treachery. Dante finds Mordred of Arthurian legend frozen in Caina, the first of Cocytus’ four zones (named after Cain of Genesis). Finally, frozen from the waist down, a three-headed Lucifer gnaws on Judas, Brutus and Cassius, chosen as the three greatest historical examples of treachery. Virgil and Dante then climb down Lucifer’s back to get to Mt. Purgatory. Added to all the contemporary thirteenth-century references, the mix is insane.

Love Poem

What struck me more than any other element of the story was Beatrice.

Dante fell in love with Beatrice Portinari when he first saw her when he was nine and she was eight. Though he seldom encountered her, he admired her from afar in what was considered the tradition of courtly love even when he married another woman in 1285. She married another man in 1287.

When she died at the age of 24 in 1290, Dante began composing poems dedicated to Beatrice’s memory. In La Vita Nuova (1293), he wrote: “Behold, a deity stronger than I; who coming, shall rule over me,” and "She has ineffable courtesy, is my beatitude, the destroyer of all vices and the queen of virtue, salvation."

Dante places Beatrice in the highest sphere of Heaven, and it is she who has importuned the almighty to enable his journey through the realms of the afterlife while still being allowed to return alive. When Virgil can go no further, it is Beatrice who guides Dante from Earthly Paradise through the spheres of Heaven, finally assuming her place in the highest sphere next to God himself. Upon meeting her again, Dante castigates himself for ever having looked to anyone but her:

|

So she said to me: ‘In the midst of my wishes Which were leading you to a love of the good Beyond which there is nothing to aspire to,

What pitfalls or what barriers did you find Across your path, that you had to give up hope Of being able to go any further?

What attractions or what advantages Showed themselves in the looks of the others That you should walk up and down in front of them?’

… Weeping I said: ‘The things that were at hand, With their false pleasure, turned my steps aside As soon as your face had gone from sight.’

—Purgatorio XXXI |

He elevates this woman to near-godhood, taking every opportunity to gush over her appearance and influence:

|

[Beatrice] began, shining upon me with a smile Which would have made a man in flames happy:

—Paradiso VII |

|

…looking into those lovely eyes From which love had made a noose to catch me.

—Paradiso XVIII |

I couldn’t help but feel for the lifelong longing Dante experienced—so deep that he continued to write about her decades after she died. I wondered whether the entire effort of the Divine Comedy wasn't simply an attempt to reconstruct her so that he could meet her again, and whether most readers are aware that this entire endeavour, from Hell to Heaven, may indeed be nothing more than the most epic love poem ever conceived.

Beatrice leaves Dante only at the very end, right before he comes face-to-face with the Light of God.

Philosophical Argument

Throughout the Comedy, Dante propounds a powerful philosophical, moral and political point. In addition to expressing his dissatisfaction with the contemporary world, he offers lengthy Platonic discussions on freewill and the role of earthly power in holding mankind to the laws of Heaven, and offers a concrete outline of the separate roles of spiritual church and earthly empire, beneath which he has a firm belief in a primal truth that cannot be explained through human reasoning.

Although people who never existed occupy a variety of positions in the Inferno, Dante always claimed that his journey from Hell to Heaven had actually physically occurred, and was neither a vision nor any kind of fictional invention. He believed, in fact, that he was writing a text that would guide mankind out of lassitude into a righteous future:

|

Take note: and as my words are carried from me, Make sure that they are delivered to the living Whose life is nothing but a race to death.

—Purgatorio XXXIII |

He was a scholar, philosopher and moralist who commented on the duty of writers, the impermanence of fame, the desire for immortality through art, and peppered his mile-long similes with detailed knowledge of science, astronomy, geometry and optics:

|

And if I am a timid friend to truth, I fear to lose the life I may have among those Who will call the present time, ancient times.

—Paradiso XVII |

|

O empty glory of human endeavour! How little time the green remains on top, Unless the age that follows is a dull one!

—Purgatorio XI |

|

O my dear root, and yet so far above me That, as an earthly mind can understand A triangle cannot have two obtuse angles,

You see things which are contingent Before they exist, looking upon that point To which all times are present;

—Paradiso XVII |

In addition to discussing psychology and the processes of spiritual repentance, Dante even considered God’s motivation for creating the universe:

|

Not to obtain any more good himself, Which is impossible, but so that his splendour Might as it shone back, declare: “I am,”

—Paradiso XXIX |

Finally, he devised an elaborated reworking of the Lord’s Prayer, recited at the first of Mt. Purgatory’s seven cornices, where the proud walk in circles, each bearing crushing loads of stone. I found it remarkably evocative.

|

Our father, which art in heaven, Not because circumscribed, but out of the greater love You have for your first creation on high,

Praise be to your name and worthiness From every creature, as it is appropriate To render thanks to your sweet charity.

Thy kingdom come, and the peace of thy kingdom, Because we cannot attain it of ourselves, If it does not come, for all our ingenuity.

As of their own freewill your angels Make sacrifice to you, singing Hosanna, So may men also do of their freewill.

Give us this day our daily manna, Without which, through the roughness of this desert, He who tries hardest to advance, goes backward.

And as we forgive everyone the evil That we have suffered, may you pardon us Graciously, and have no regard to our merits.

Do not put our virtue to the test With the old adversary, it is easily overcome, But free us from him who spurs us on.

Make for ourselves, having no need of it, But for those who are left behind us.

—Purgatorio XI |

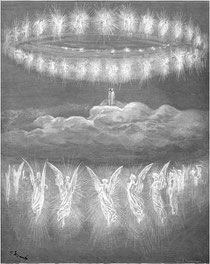

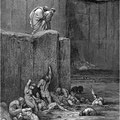

The translation I read was by C.H. Sisson, Oxford World’s Classics. More of Gustave Doré's illustrations can be found here.

Write a comment

Ryan Morton (Tuesday, 24 July 2012 06:12)

Hi Mike,

Great little essay/review. I might just have to pull that out and read it. I'm not sure if my copy includes the context notes though. I read Thomas Moore's Utopia a while back. It was also written as if from the experiences of the author while on a tour of the lands in question. It seems to be a convenient style for political/social commentary. Too bad we don't see much first person narrative in popular media these days.

Peace,

Ryan

thekanert (Wednesday, 25 July 2012 05:58)

The Oxford World Classics version has some very good and essential endnotes. They elaborate on a number of unnecessary bits as well, but overall it's needed for the context.

Now the style has shifted more to science fiction--which is essentially what these works were. They were fantasy. However, fantasy had yet to develop to the state of creating full alternative worlds, so they just envisaged different realms within this world, and presented themselves as travelers who had returned from those realms. We see the first person come up more in psychological dramas exploring the human mind or paranormal phenomena, which I imagine is partly a result of the fact that fantasy is more about pretending to be someone else in a different world rathern than just being your boring old self and experiencing a world that you cannot really affect. I think also travelogues are less in favour than they were back when the world was still being discovered and it seemed like any sort of place could exist anywhere.